For decades, North Carolina Central University has produced world-class athletes, and it’s time to give NCCU its flowers! Learn about the athletes that represented NCCU well in Olympic arenas in the full story from Lewis Bowling at the News & Observer below.

Lee Calhoun stood at the start line of the Olympic 110-meter hurdles. An underdog, Calhoun was not content just to compete in the event that every four years plays host to the best athletes in the world. Calhoun, the first athlete from North Carolina Central University to qualify to participate in the Olympics, wanted to return to the Durham campus as the best 110-meter hurdler in the world.

Tokyo? Hardly.

These Olympic Games were in Melbourne, Australia. This was 1956.

Standing close to Calhoun, ready to compete in the same event, was a good friend from Duke University, Joel Shankle. Calhoun and Shankle were training partners in Durham.

In 1956, it was not common to see Black athletes participating alongside white athletes, much less training side by side. But that’s what Calhoun and Shankle did. Dr. Leroy Walker, the track coach at NCCU, and Bob Chambers, the track coach at Duke, got together and agreed that Calhoun should train at what was then called Duke Stadium — now Wallace Wade Stadium — with Shankle. With NCCU’s and Duke’s campuses separated by just a few miles, it made sense that these two world-class athletes who specialized in the same event should train together. Good competition in practice makes athletes push themselves to new limits, they figured.

Standing close to Calhoun, ready to compete in the same event, was a good friend from Duke University, Joel Shankle. Calhoun and Shankle were training partners in Durham.

In 1956, it was not common to see Black athletes participating alongside white athletes, much less training side by side. But that’s what Calhoun and Shankle did. Dr. Leroy Walker, the track coach at NCCU, and Bob Chambers, the track coach at Duke, got together and agreed that Calhoun should train at what was then called Duke Stadium — now Wallace Wade Stadium — with Shankle. With NCCU’s and Duke’s campuses separated by just a few miles, it made sense that these two world-class athletes who specialized in the same event should train together. Good competition in practice makes athletes push themselves to new limits, they figured.

MAKING A NAME FOR HIMSELF

Calhoun was born in 1933 in the heart of the South in the small town of Laurel, Mississippi. Even though he was thousands of miles away from home, at the start line of the 110-meter hurdles in Australia, Calhoun was full of confidence.

Calhoun first made a name for himself May 10, 1952, at the CIAA Track and Field Championships, competing for NCCU, then known as North Carolina College. He finished first in the 120-yard high hurdles and the 220-yard low hurdles. In 1953 at the Evening Star Track Meet in Washington, D.C., he beat Shankle in the 70-yard high hurdles. Calhoun’s national acclaim found a spotlight when he won the 120-yard high hurdles at the Penn Relays in 1953, where most of the country’s best track stars competed. In 1956, before the Olympics that year, Calhoun tied the world record in a meet in Philadelphia in the 50-yard high hurdles with a time of 6.0 seconds. He again beat Shankle and also beat another top hurdler in the world in Harrison Dillard. The next day, Calhoun won the 70-yard high hurdles in 8.3 seconds, tying the world record. At a track meet in Durham, he won the 100-yard dash, not his specialty.

Calhoun had already brought notoriety to the NCCU campus by winning an NCAA championship in the 120-yard hurdles earlier in 1956 in Berkeley, California (and he won that NCAA event again in 1957). Calhoun had also won the AAU 110-meter hurdles in 1956. Along with that, he knew that Shankle, his friend and training partner from Duke, was also one of the fastest hurdlers in the world, and they had run against each other many times. Another reason for Calhoun to be confident was that he had been tutored by one of the best track coaches in the United States at the time, NCCU’s Walker.

THE BIG RACE AND ITS AFTERMATH

In the 110-meter hurdles at the 1956 Olympic Games, Calhoun exploded out of the start line, with Shankle just behind him in the lane to his left. Calhoun was being closed in on by his United States teammate, Jack Davis. At the finish line, Calhoun lunged his shoulders forward and crossed the line in 13.5 seconds, a new Olympic record. Jack Davis had also finished in 13.5 seconds, and Shankle finished in 14.1 seconds. Shankle won the bronze medal.

Calhoun’s lunge forward at the finish line won the gold medal; he was the best in the world in the 110-meter hurdles.

Upon their return to Durham, Calhoun and Shankle were treated like heroes. A throng of fans, many from NCCU, greeted them at the airport. A motorcade was formed from Raleigh-Durham Airport to carry the two athletes to Durham, where a parade was held on Main Street. Bands from NCCU, Duke and local high schools marched down streets full of people. Calhoun and Shankle were presented keys to the city by Durham Mayor E.J. Evans.

AN OLYMPIC LEGACY

Edwin Roberts brought more track and field glory to NCCU at the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, where he won the bronze medal in the 200-meter dash and another bronze medal in the 4×400-meter relay. From 1956-1976, an Eagle student-athlete represented NCCU in every Olympic Games.

Roberts also competed in the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, but did not medal, although he finished fourth in the 200-meter dash. Norman Tate of NCCU competed in the triple jump in the 1968 Olympics Games in Mexico City. Also in the 1968 Olympics, Roberts competed again. In the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Germany, Roberts ran in his third straight Olympics. NCCU’s Larry Black won a gold medal in the lead leg of the 4 by 100-meter relay and won a silver medal in the 200-meter dash with a time of 20.19. Julius Sang and Robert Ouko, also NCCU student-athletes, earned gold medals as part of the 4×400- meter relay team. Sang also won a bronze medal in the 400-meter dash with a time of 44.92. In the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, Canada, NCCU’s Charles Foster placed fourth in the 110-meter hurdles with a time of 13.41.

Having Olympians from NCCU in six consecutive Summer Olympics from 1956 to 1976 was an accomplishment attained by few universities, and the streak would almost certainly have continued had the United States not boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics in protest of the Games being held in Moscow, after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan.

This long line of NCCU track and field Olympians all competed under Walker’s direction. He also served as head coach for the United States men’s track and field team in the 1976 Olympic Games, and went on to become the first Black president of the United States Olympic Committee.

On the coaching side, former NCCU men’s basketball coach John McLendon, who coached at NCCU in the 1940’s and early 1950’s, was chosen as the first Black assistant coach on a United States Olympic basketball team for the 1968 Games in Mexico City. The basketball arena on the NCCU campus is in part named for him.

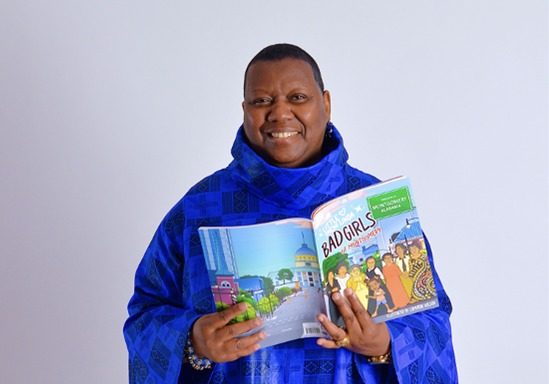

Amba Kongolo, one of the best women’s basketball players to ever play at NCCU, also represented NCCU in the Olympics, playing for the Zaire Olympic team in Atlanta in 1996.

As this year’s edition of the Olympics comes to a close in Tokyo, with athletes representing North Carolina across several events, one small campus in Durham can claim with pride to have contributed mightily to the U.S. teams on the Olympic stage.